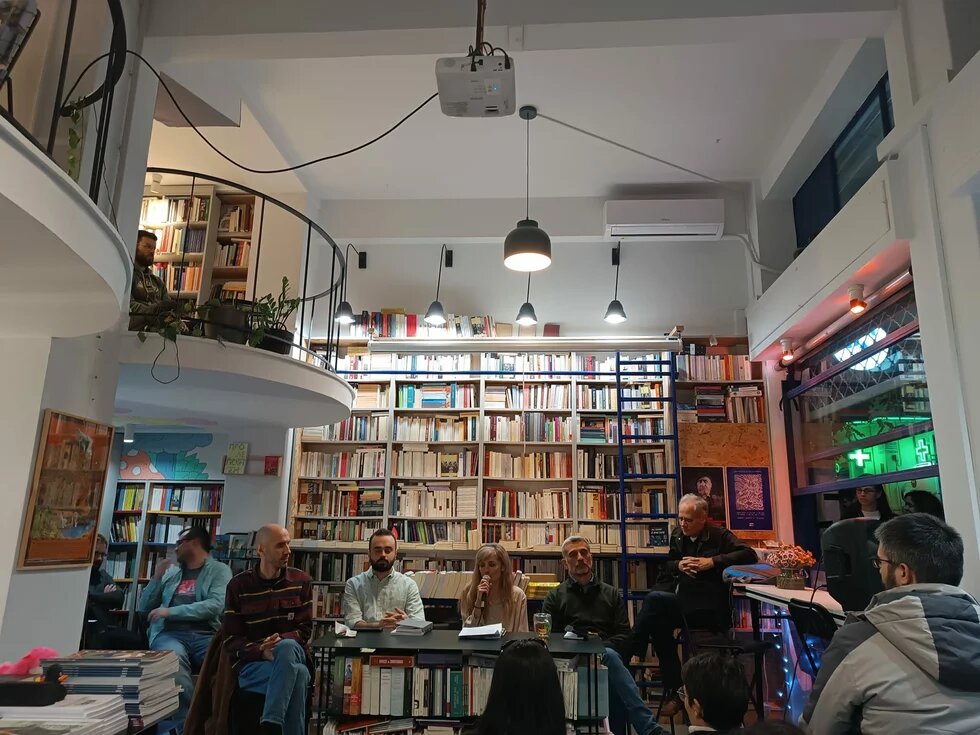

How does technology shape people’s everyday lives? Does it contribute (if at all) to social development? Does it promote democracy? Does it break down social and cultural stereotypes, or does it conform to them? These and many more questions are brought to light in the publication “In front of the technological mirror – Analyzing the social reflections of technology”. The book, a project by the Sociality team in collaboration with Open Lab Athens and published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation – Thessaloniki Office, was presented on November 5, 2024, at the packed “Komprai” bookstore in Athens.

The publication emerged from a series of four podcasts that aimed to popularize the conversation around contemporary techno-social challenges such as artificial intelligence, platforms and algorithms, surveillance, the ethics of technology, and many more. Specifically, the book includes transcribed excerpts from audio interviews and expert commentary, as well as the results from related workshops that preceded it, and also an appendix on the portrayal of technology in literature.

“Often, we don’t ask what the side effects are”

The publication was thoroughly presented by Antonis Faras, a member of Sociality, a technology cooperative that began as a digital tech co-op and has now been active for 10 years. As he explained, the creation of the publication was driven by the importance of exchanging ideas on issues that arise when technology intersects with society. “We often view technology as a linear development process and rarely ask what the side effects are”, he remarked. The publication aims to plant a seed in the discussion of a range of issues such as the definition and challenges of technology, the emergence of artificial intelligence and its implications for the future of work, its social and political dimensions, the relationship between technology and gender, the rise of the platform economy, and the influence of technology on art or vice versa. “The goal is to highlight these issues and questions, without necessarily demanding answers”, said Antonis Faras.

Would you implant a chip to get a job?

Giannis Zgeras, from the research and technology lab Open Lab Athens, spoke about the results of the participatory workshops that preceded the podcasts and were held in Ioannina and Thessaloniki. One of these explored, through experiential methods, how technology affects people’s realities, with a focus on whether social media can shift their political views. The second workshop was centered on dystopia, as participants were asked to work through two scenarios.

In the first scenario, an implant is required for access to the job market while in the second, a powerful algorithm scans the internet and decides the next government based on comments on social media. Following this, the authors of the publication developed a “collective mental map of our digital lives”, essentially a mapping of our daily life through our interaction with technological devices and digital services. “In the future, we or others will have the opportunity to pick up the thread of this publication and carry it forward”, concluded Giannis Zgeras.

“Not even housecleaning”

Technology has not only failed to free us from the burden of labor, but it hasn't even managed to resolve simpler issues, like housecleaning. “This fantasy of an automated, somewhat lazy life of pleasures without work has not succeeded”, said Aliki Kosyfologou, PhD in Political Science and Sociology at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, researcher, and author of the book “Elusive motherhood: contemporary aspects of motherhood in times of crisis”. As she noted, technology, as a process involving applications and usage, carries political weight, since it requires human labor.

Aliki Kosyfologou made special reference to Evelyn Fox Keller’s article “Feminism and Science”, which is extensively discussed in the publication. As she explained, the article “introduced the feminist perspective into the study and analysis of science and technology, highlighting a structurally androcentric dimension that often makes science appear inaccessible and mysterious”. Keller herself, far from being technophobic, suggests that the collective effort to improve the world through knowledge should continue, albeit on better foundations. Aliki Kosyfologou believes that “a good way to approach Keller’s vision is to anchor ourselves in utopia and in the conviction that science and technology can improve living conditions in society”.

“You can write whatever you want, but no one will see it”

“Is the toilet flush technology?”. This provocative question, posed in the podcasts and in the book, was the starting point for journalist Konstantinos Poulis, from The Press Project. Author of the book “From the plough to the smartphone: Conversations with my father”, Poulis had dedicated a chapter in his own work to the toilet – a topic he described as one of applied biopolitics. But if technologies related to everyday life are the least controversial, communication technologies are highly contested, he noted. “All communication technologies throughout modernity have been accompanied by the promise of greater, deeper, more radical democracy, supposedly because they facilitate the dissemination of information. This was the case with printing press, newspapers, radio, television, and of course with the personal computer, the internet, and social media”. However, that never happened, and it is not happening now.

Regarding artificial intelligence, he highlighted that there is a hidden material world behind it and cited the example of child labor in Congo, where six-year-old children work under inhumane conditions in mines to extract raw materials for companies that promise a future where technology ‘frees our hands’. As for platforms, he stated that “they don’t just exploit people, they crush them like cigarette butts on the pavement”, noting that the promise of horizontality has been overturned across all platforms, from music to pornography, since those who benefit are only the already successful at the top. He also raised the issue of transparency, noting that communication algorithms are secret, no one knows how they work, and that this is the way that allows companies to evade accountability. “They can know everything about you, but you know nothing about them”, he remarked, adding that this plays a key role in information control: “As a journalist, you can write whatever you want, be happy you wrote it, but it might be something no one ever sees”.